Business

Rebuilding America: High-Speed Rail

Rebuilding America: High-Speed Rail

HSR can spur economic growth and revitalize American industry.

By: Gerald Lee 𝕏 | 07/08/2024

Consider donating to support AF Post

From long before the completion of the first Transcontinental Railroad in 1869 to the conclusion of the Second European Civil War in 1945, railroads quite literally built America into the industrial colossus it was always meant to be. When one sees a small town that appears to be non-sensibly located in the “middle of nowhere,” chances are that there used to be a train station in the area, and a few dozen folks decided to put down some permanent roots there. A new town was born.

So, where did all these railroad lines go? Without writing out a 30-page white paper on the subject, the diversion of infrastructure resources towards highways and car infrastructure, generally by automobile lobbies, strangled the railroads on the short-distance travel end and airlines on the long-distance end.

While the air travel side of the equation can certainly be chalked up to the inevitability of creative destruction as technology progresses, that does not explain away the disappearance of railroads for short and medium distance travel.

America was lobbied out of improving its transit systems.

In fact, GM went so far as to make and distribute a literal propaganda film that assisted tremendously in establishing the Interstate Highway System (far beyond what was deemed militarily necessary) and the car-centric suburban sprawl that blights every American city today.

Meanwhile, the then-dirt poor nation of Japan, barely recovered from the devastation of their thorough defeat in 1945, initiated the construction of the world’s first high-speed line in 1959, which opened in time for the 1964 Olympic Games. Today, Japan has already set up plans to go beyond even high-speed rail, constructing the world’s first intercity maglev line. When completed, it will make the distance between Tokyo and Osaka, Japan’s two largest cities, commutable in about one hour. This is roughly the same distance as Chicago to Detroit or DC to New York.

Many argue that America differs greatly from Japan, as it is much more spread out than the relatively small island in the Pacific. However despite the vastness of our continent, the introduction of high-speed rail or maglev line would still have a beneficial effect on simple demographics and economic development.

The remainder of this century will be a very rough ride from a demographic perspective. America has been reproducing at below replacement rates for half a century. And now we are running out of people under fifty to fill in the traditional employment slots in the economy.

At the same time, in order to stave off civilizational competition from China, the only true civilizational rival to the West, we must continue to move Western economies further up the value-added chain. This can be done through international cooperation with the rest of the West, but that component has already been discussed. Another component to overcoming this challenge would be to integrate as many major cities as possible in order to pool as many skilled workers as possible into a single functional labor market.

For example, a top computer science graduate from, say, Germany might not be interested in moving to Chicago to contribute to a budding quantum computing industry there due to the extremely high costs of living. However, he might be far likelier to be willing to relocate to Indianapolis if he could conveniently commute into and out of Chicago. This allows such a graduate to spur the economy while also having the means to single-handedly support a family. Giving highly skilled workers such options will not only allow the nurturing of cutting-edge industries in regional hubs like Chicago, New York City, and Los Angeles, but it will also ease housing pressures in these major urban centers. This is until we kickstart a property construction boom in the major cities, of course.

The necessity of such transportation systems will become increasingly apparent when Zoomers, the smallest generation in American history as a percentage of the population, mature and start to occupy non-entry-level positions over the next few decades. The sooner we as a nation plan for this eventuality, the better off we will be as a society and vis-a-vis our competitors, i.e. China.

Maglev in America

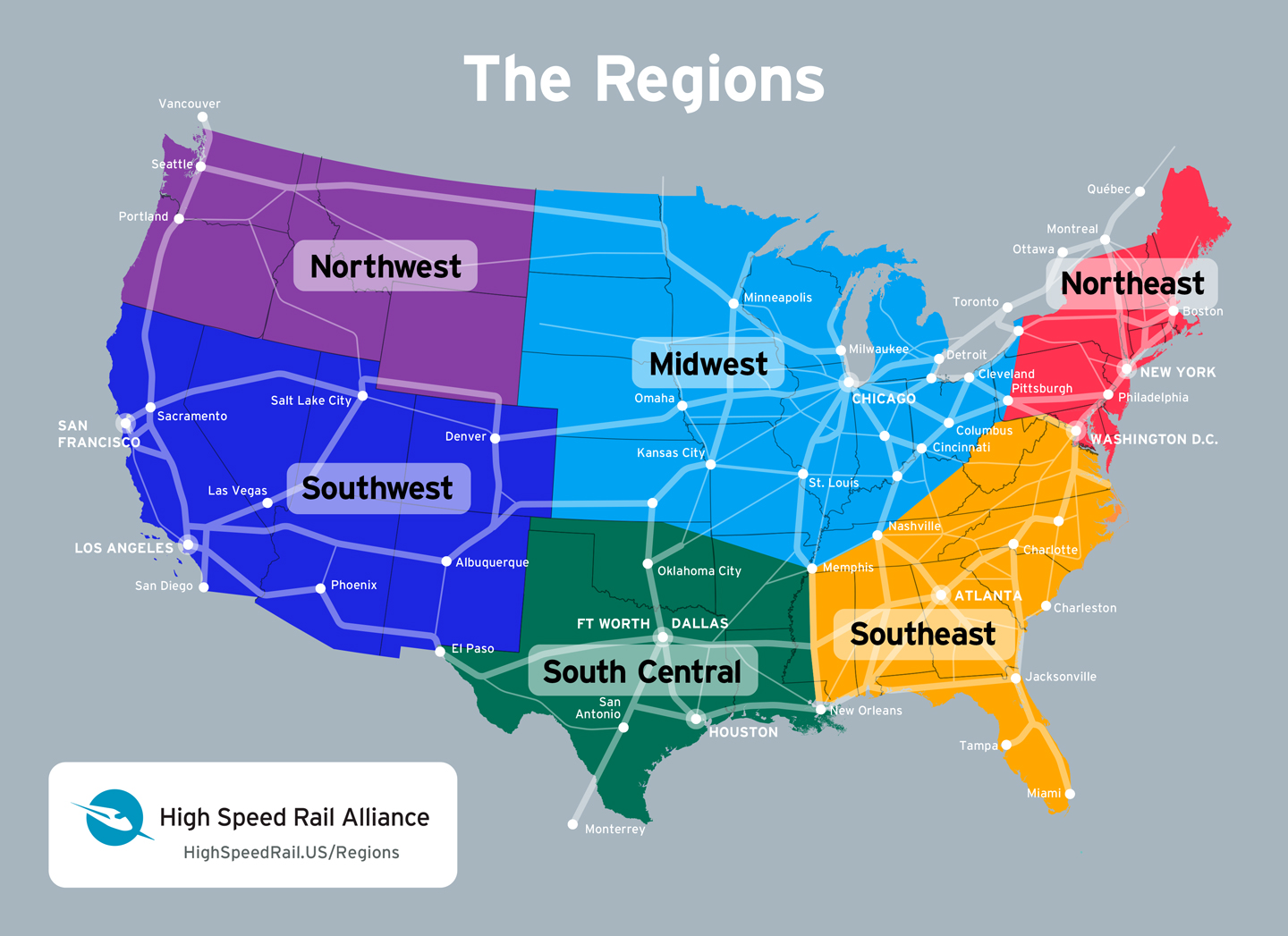

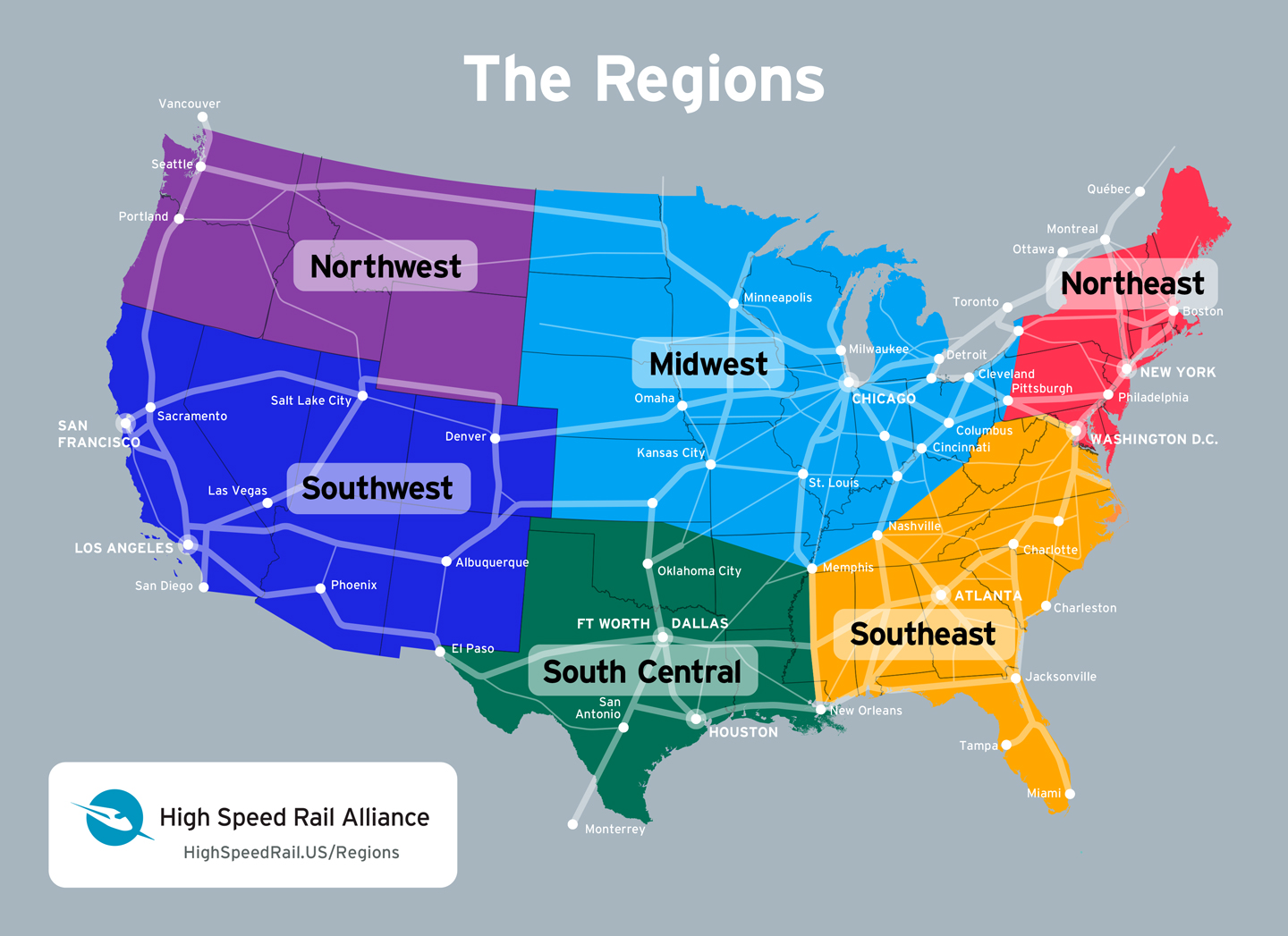

The best course of action would be to focus on connecting all metro areas with populations of over a million in the continental United States. As of the writing of this piece, that would be fifty-three metro areas. Even if we were to include connecting Vancouver and the Windsor-Quebec City corridor with this network, which would include the majority of Canada’s entire population, we would need somewhere in the neighborhood of twenty thousand miles of HSR track. For context, China has already built north of thirty thousand miles.

Even at the most conservatively high estimates of cost, a hundred million dollars each mile, including land acquisition, this project would cost a hundred billion dollars annually over a twenty-year construction period, barely 1/60 the federal budget at this point. If we are doomed to spend astronomical amounts of money through the federal purse, we might as well have something to show for it.

The curious thing is that, even if we were to care about turning a profit on a national HSR system, something never required of the Interstate Highway system, mind you, this can easily be done by integrating passenger rail lines with either freight lines, revenues from real estate in the immediate vicinity of train stops, or both.

Indeed, combining freight and passenger operations was how trains in America have historically turned a profit. For context, the U.S. freight costs are 1.2 trillion per year, and these maglev trains could significantly increase the efficiency and speed of much of the U.S. freight system. Increasing the efficiency of such a large industry could alone pay back the cost of the project.

Regarding using adjacent real estate revenues, this is exactly what the Japanese and Hong Kong systems do. It is no surprise that these two systems are some of the most well-run and profitable systems in the world. In fact, real estate profits were what kept the Tokyo system afloat during the pandemic when ridership temporarily nosedived.

America was not actually built by or for the car. If anything, American cities were bulldozed for the car. While railroads are not a panacea for all our transportation woes, as no one solution would, they undoubtedly represent a vital component to a truly First World national transportation network that we must no longer neglect and underinvest in.

So, where did all these railroad lines go? Without writing out a 30-page white paper on the subject, the diversion of infrastructure resources towards highways and car infrastructure, generally by automobile lobbies, strangled the railroads on the short-distance travel end and airlines on the long-distance end.

While the air travel side of the equation can certainly be chalked up to the inevitability of creative destruction as technology progresses, that does not explain away the disappearance of railroads for short and medium distance travel.

America was lobbied out of improving its transit systems.

In fact, GM went so far as to make and distribute a literal propaganda film that assisted tremendously in establishing the Interstate Highway System (far beyond what was deemed militarily necessary) and the car-centric suburban sprawl that blights every American city today.

Meanwhile, the then-dirt poor nation of Japan, barely recovered from the devastation of their thorough defeat in 1945, initiated the construction of the world’s first high-speed line in 1959, which opened in time for the 1964 Olympic Games. Today, Japan has already set up plans to go beyond even high-speed rail, constructing the world’s first intercity maglev line. When completed, it will make the distance between Tokyo and Osaka, Japan’s two largest cities, commutable in about one hour. This is roughly the same distance as Chicago to Detroit or DC to New York.

Many argue that America differs greatly from Japan, as it is much more spread out than the relatively small island in the Pacific. However despite the vastness of our continent, the introduction of high-speed rail or maglev line would still have a beneficial effect on simple demographics and economic development.

The remainder of this century will be a very rough ride from a demographic perspective. America has been reproducing at below replacement rates for half a century. And now we are running out of people under fifty to fill in the traditional employment slots in the economy.

At the same time, in order to stave off civilizational competition from China, the only true civilizational rival to the West, we must continue to move Western economies further up the value-added chain. This can be done through international cooperation with the rest of the West, but that component has already been discussed. Another component to overcoming this challenge would be to integrate as many major cities as possible in order to pool as many skilled workers as possible into a single functional labor market.

For example, a top computer science graduate from, say, Germany might not be interested in moving to Chicago to contribute to a budding quantum computing industry there due to the extremely high costs of living. However, he might be far likelier to be willing to relocate to Indianapolis if he could conveniently commute into and out of Chicago. This allows such a graduate to spur the economy while also having the means to single-handedly support a family. Giving highly skilled workers such options will not only allow the nurturing of cutting-edge industries in regional hubs like Chicago, New York City, and Los Angeles, but it will also ease housing pressures in these major urban centers. This is until we kickstart a property construction boom in the major cities, of course.

The necessity of such transportation systems will become increasingly apparent when Zoomers, the smallest generation in American history as a percentage of the population, mature and start to occupy non-entry-level positions over the next few decades. The sooner we as a nation plan for this eventuality, the better off we will be as a society and vis-a-vis our competitors, i.e. China.

Maglev in America

The best course of action would be to focus on connecting all metro areas with populations of over a million in the continental United States. As of the writing of this piece, that would be fifty-three metro areas. Even if we were to include connecting Vancouver and the Windsor-Quebec City corridor with this network, which would include the majority of Canada’s entire population, we would need somewhere in the neighborhood of twenty thousand miles of HSR track. For context, China has already built north of thirty thousand miles.

Source: High Speed Rail Alliance

Even at the most conservatively high estimates of cost, a hundred million dollars each mile, including land acquisition, this project would cost a hundred billion dollars annually over a twenty-year construction period, barely 1/60 the federal budget at this point. If we are doomed to spend astronomical amounts of money through the federal purse, we might as well have something to show for it.

The curious thing is that, even if we were to care about turning a profit on a national HSR system, something never required of the Interstate Highway system, mind you, this can easily be done by integrating passenger rail lines with either freight lines, revenues from real estate in the immediate vicinity of train stops, or both.

Indeed, combining freight and passenger operations was how trains in America have historically turned a profit. For context, the U.S. freight costs are 1.2 trillion per year, and these maglev trains could significantly increase the efficiency and speed of much of the U.S. freight system. Increasing the efficiency of such a large industry could alone pay back the cost of the project.

Regarding using adjacent real estate revenues, this is exactly what the Japanese and Hong Kong systems do. It is no surprise that these two systems are some of the most well-run and profitable systems in the world. In fact, real estate profits were what kept the Tokyo system afloat during the pandemic when ridership temporarily nosedived.

America was not actually built by or for the car. If anything, American cities were bulldozed for the car. While railroads are not a panacea for all our transportation woes, as no one solution would, they undoubtedly represent a vital component to a truly First World national transportation network that we must no longer neglect and underinvest in.